People don’t connect the dots between lower gasoline prices and the shale oil boom.

Yesterday I filled my gas tank for $23.70, with the per gallon price in the mid-$2.40 range. That’s not low compared to when I commuted to Eldridge and fueled at Walcott for $1.02 per gallon for what seemed like months. Neither is it like when I was young and gas wars yielded prices below $0.30, enabling me to top off my tank for a buck or two. However, we are now below $3 per gallon with the prospect of going lower, so prices seems low in a short-term, relativistic way.

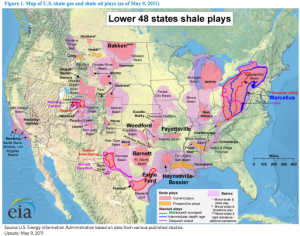

There is no doubt that the revolution in shale oil production through hydraulic fracturing is causing the lower oil and natural gas prices in the U.S. The shale boom is replicable world-wide (at least to some degree) because shale is a common and abundant form of sedimentary rock. In some ways, the game changing of shale is just getting started, even though it began in the 1940s.

When I was in my 20s, we thought shale oil was inaccessible. Hydraulic fracturing is a technology that revolutionized exploration, development and production of shale oil. In light of higher oil prices, it became profitable. Some credit goes to politicians, but most credit goes to the oil companies who persistently lobbied for a relaxed regulatory environment with anyone who could be influenced from the president on down.

What does this mean besides lower gasoline prices? Three things seem most important.

The arguments for and against hydraulic fracturing are reasonably accessible.

“Hydraulic fracturing is highly controversial, proponents advocating economic benefits of readily accessible hydrocarbons, and opponents concerned for the environmental impact of hydraulic fracturing including contamination of ground water, depletion of fresh water, degradation of the air quality, the triggering of earthquakes, noise pollution, surface pollution, and the consequential risks to health and the environment,” according to Wikipedia.

There is plenty of meaning in the existential fact of hydraulic fracturing and use of its products. What is less discussed is the impact on climate change, and the impact on renewable energy development.

While shale oil production is booming, 2014 will be the warmest year on earth since record-keeping began, and a clear departure from the climatic conditions in which the industrial revolution emerged. It’s hot and getting hotter world-wide. The climate has changed and is changing.

It is a scientific fact that man-made pollution is contributing to the warming planet. Natural gas is a fossil fuel that emits carbon dioxide when burned. While part of domestic carbon emission reductions during the last ten years have come by switching from coal to natural gas for electricity generation, there are problems.

Methane released as a byproduct of hydraulic fracturing operations is a more potent greenhouse gas than CO2. Methane leakage would reduce the value of the air pollution reduction realized by shifting electricity production from coal to natural gas. Some say methane leakage could negate any gains made in CO2 reductions from switching from coal to natural gas.

As a fossil fuel, natural gas should be viewed only as a so-called bridge fuel, although the clear and present danger is that it will be perceived as a destination fuel and become a permanent fixture in our energy mix.

That raises the third issue. There is a broader economic impact that the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (BAS) spelled out in a Dec. 10, 2014 article. Not only is gasoline cheap in a shale gas development scenario, it is impacting the U.S. energy mix, and nuclear power and renewables are taking the hit.

The basic argument about bridge fuels is that the shale boom and its products can act as “bridge” fuels, curbing emissions while non-fossil energy sources such as renewables and nuclear energy are ramped up.

As we have seen in Iowa, new nuclear power has become financially untenable unless its excessive costs can be passed along to rate payers.

Not only are new nuclear power plants imperiled because of the economics of the shale boom, existing nuclear plants have been as well. “While cheap gas is not the only culprit eroding the profitability of nuclear energy, it is the straw that is breaking the camel’s back,” wrote BAS.

What’s more important is the economics of shale gas are suppressing development of renewable energy. As we have seen in Iowa, without government subsidies of renewable energy, production of new renewable capacity languishes. In the current political climate, it is uncertain whether renewable energy subsidies will continue, and for how long.

While the economics of wind and solar may be reaching parity with fossil fuels in some markets, we are not there yet, and the subsidies are essential to continuing development of alternatives to fossil fuels.

It is important that we extend our reach beyond personal or family budgets and do what is right about the shale boom. That means developing the political will to finish a transition to a fossil fuel free world.

Easier said than done, but the price society will pay for failing to do so is much higher than what we see at the gas pump.